by Owen Thomas

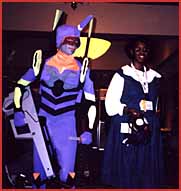

"Sailor Moon, Sailor Mooooon," two young girls call out as they run towards their idol who stops to pose for their cameras. Moments later it's, "Miyu, Miyu," and they trot thirty feet to meet Vampire Princess Miyu who strikes a glamorous pose while the girls take turns photographing each other with her. When asked why they're so excited, their brows furrow a bit as if suspicious that I am an imbecile before the taller of them replies simply, "Because that's Sailor Moon." When I follow up by pointing out that actually it's just an anime fan in a costume, their sighs indicate that their suspicions have been confirmed. My admittedly tenuous grasp of normal behavior clearly doesn't apply within the cloistered walls of this sub-cultural epicenter. Alexander de Toqueville wrote that in order to understand Americans one must first understand their games. He meant baseball, but in order to understand the modus vivendi within the convention I would first have to understand their favorite pastime. At anime conventions across the continent renowned writers, artists, directors and voice actors draw throngs of fans to hear them speak; and at virtually every convention they nonetheless play second fiddle to the real stars of anime- the characters they've created. Anime convention floors teem with anime fans costumed as Vash, Tenchi, Pikachu, the penguin from Evangelion, or Sailor Moon. Especially Sailor Moon. At the Anime Expo 2000 held at the Disneyland Hotel it wasn't unusual to see a dozen or more Sailor Moons in the same line waiting for a movie or a panel. And every one of them, along with the Miyus, Mononokes, Cowboy Bebop gangs, and even the penguin, is treated like a star- even though everyone knows (apparently without my having to point it out in the middle of interviews) that they aren't. Such is the nature of cosplaying: anime fans playing an elaborate game whose rules are unspoken yet understood by seemingly all the convention attendees. T-shirt-and-jeans-clad con goers and vendors call out to the cosplayers by their characters names; gush about how wonderful "their" show or movie is; compliment them for their characters' heroism, humor, or appeal; and occasionally burst into spontaneous applause when the cosplayers in turn strut and pose in the style of "their" character, perhaps even dramatically declaiming the characters best-known lines. Everyone, whether in costume or not, plays along with relish. After all, pretending to meet and be photographed with your favorite stars is every bit as much a fantasy as being a star. As ubiquitous as cosplay is at today's anime conventions, virtually no one knows when it started, or how and why it has become the dominant feature of the convention experience. The term "cosplay" was adopted from the Japanese, "Kosupura." In Japan cosplay is even more popular than in America, and isn't confined only to conventions. Nightclubs, movie premieres, and comic markets attract costumed anime fans by the tens of thousands. But even in this country the pastime dates back further than anime conventions, back through their predecessors- the science fiction film and television, or just plain animation convention- and beyond. Ages ago, in a world few anime fans today would even recognize- before "Gundam," before Atari, even before "Star Wars"- fans of science fiction books and fantasy role-playing games attended conventions in costumes. Cosplay's popularity has proven durable, whatever the motivations behind it may be.

Psychologist Dr. Delphine DeMore, a therapist in the Los Angeles area, notes that cosplaying, under whatever guise, has a widespread appeal because it gives participants a chance to step out of their usual identity. By pretending to be someone whom they aren't, cosplayers get a different perspective on themselves, and their own "normal" behaviors and personalities. She also notes that although a cosplayer with certain neuroses might bring those neuroses into the game with him, thereby making the hobby unhealthy, for most cosplayers costuming is probably good healthy recreation. To many convention attendees the cosplayers are the closest anyone not living in Cool World or Toon Town will come to meeting the stars of their favorite movies. As convention-goer Beverly Alliss put it, "It's like seeing a character you love in person, even though you know better. It's the next best thing." The fact that these stars make themselves available for photographs, questions, even autographs, apparently makes up for the small matter that they may actually be high school students with sewing machines, or office workers with active imaginations. At virtually every convention in the nation today cosplaying is one of, if not the single best-loved parts of the weekend. Amanda Tomasch, organizer of Aka Kon in Vancouver, admitted that, "Without the cosplay, without the extreme interest of the fans, it [a convention] would essentially be nothing but a trade show." So popular are these cosplaying events that many fans find time at the conventions between snapshots, shopping and filmgoing, to attend seminars about costuming and cosplaying. At the recent AniMagic convention in Lancaster CA, on the outskirts of the middle of nowhere, Tristen Citrine of Sailor Jamboree- a group of cosplaying friends who portray the entire Sailor scouts corps and reenact entire animated music videos- lectured a room, filled almost entirely with young girls, on the fine art of cosplaying Sailor Moon and friends. Cedrine, who could probably teach advanced wig care and dyeing at beauty college, takes her hobby seriously enough that amidst arcane details about fabric types and wig heads she could sincerely advise the room, "As soon as you're eighteen go buy leather and fetish magazines. As a costumer they're so inspirational." (Although even she couldn't quite keep a straight face.) |